PREA Quarterly Departments - Spring 2022

Introduction

Scot Bommarito

Scot BommaritoRCLCO Fund Advisors

William Maher

William MaherRCLCO Fund Advisors

The affordable housing sector, often overlooked by institutional investors, has several unique features that can make it a stable and attractive part of a diversified real estate portfolio. First, affordable housing benefits from sizable and growing demand that is unlikely to be met—affordable housing supply lags demand by large margins. This imbalance yields high occupancy, persistent rent growth, and low turnover rates, which in turn contribute to stable risk-adjusted returns.

Second, affordable housing is often considered “recession-proof.” When the economy is growing and incomes rise, affordable housing rents—tied to median income—rise in tandem; when the economy is down and incomes stagnate, demand for affordable housing grows. This attribute further contributes to the sector’s stability.

Third, the social benefits of affordable housing are valuable intrinsically and for investors’ environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals. Most pension funds are increasingly looking to achieve financial and social returns in pursuit of a “double bottom line,” and affordable housing offers an avenue to advance that goal.

This article examines these themes as well as associated risks and other considerations. Throughout the article, affordable housing refers primarily to deeply subsidized rental housing, which the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) defines as households at 60% or less of area median income (AMI). Most government housing subsidies target this level of affordable housing. The same market dynamics also generally apply to naturally occurring affordable housing, which includes households between 60% and 80% of AMI.

Affordable Housing Demand

Property fundamentals in the affordable housing space are determined by lower-priced housing supply (both single family and multifamily) and, on the demand side, by housing costs and household incomes. Because of the wide (and widening) distribution of income and wealth in the US, affordable housing has experienced exceptionally strong demand. This has been highlighted most recently as the pandemic recovery has pushed already high housing prices to new records, constraining affordability and increasing pressure in the US rental housing market.

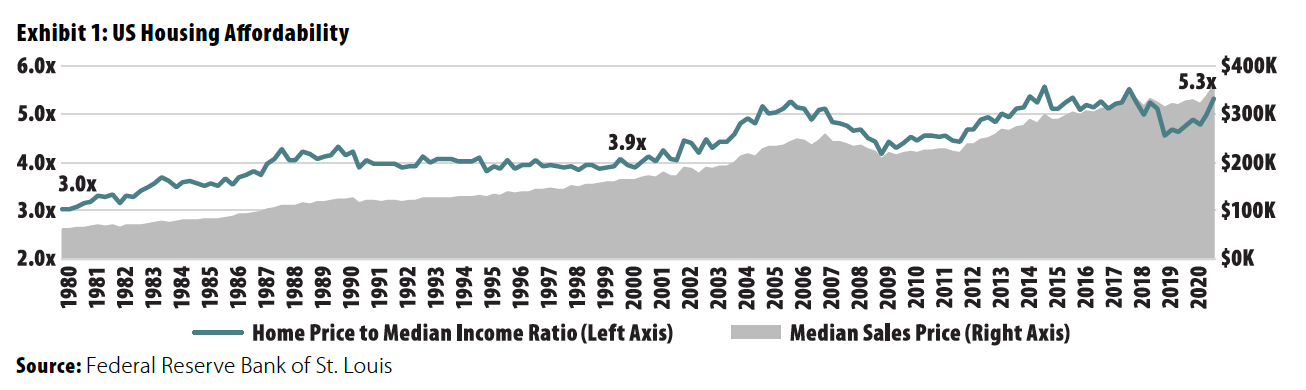

US housing prices have risen faster than inflation for the past 20 years. Real prices fell during the global financial crisis but have steadily increased over the past ten years. From 2000 to 2020, the inflation-adjusted S&P/Case-Shiller Index and FHFA Purchase Only Index each grew 44%, decreasing housing affordability especially among low-income households.1 Simultaneously, income growth among the lower quintiles of households has fallen behind growth in the top quintiles. Over the past two decades, the mean household real income of the top quintile grew 28%, while the bottom quintile’s grew only 0.3%, according to the US Census Bureau. This caused the ratio of home price to income to come close to its all-time high in 2020, with the ratio undoubtedly increasing with continued price increases in 2021 (Exhibit 1).

These trends have forced middle-income households to delay buying houses, keeping them in the rental market. This in turn has pushed rents upward, exacerbating the problem of housing affordability. Half of multifamily renter households pay at least 30% of their incomes in rent, qualifying them as “cost-burdened” by HUD, and 27% are severely cost-burdened, paying at least 50% of their incomes, indicating a plethora of renters in need of affordable housing.2

These figures include recipients of Section 8 housing choice vouchers, the largest and most direct government rent assistance subsidy, primarily assisting households with incomes below 30% of AMI. Depending on local regulations, recipients are required to contribute 30% to 40% of their monthly adjusted incomes to rent, with vouchers subsidizing the rest up to a specified maximum determined by HUD’s Fair Market Rent calculations. The other main federal affordable housing program, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), incentivizes development rather than subsidizes rents. To qualify for the credit, LIHTC properties must be at least 20% occupied by tenants at or below 50% of AMI or 40% occupied by tenants at or below 60% of AMI. There are no direct rent regulations on LIHTC units, but landlords must keep rents low enough to be able to meet the occupancy requirements. HUD updates AMI annually for each metropolitan area and nonmetropolitan county; consequently, the qualifying income thresholds for Section 8 and LIHTC tenants adjust every year.

Affordable Housing Supply

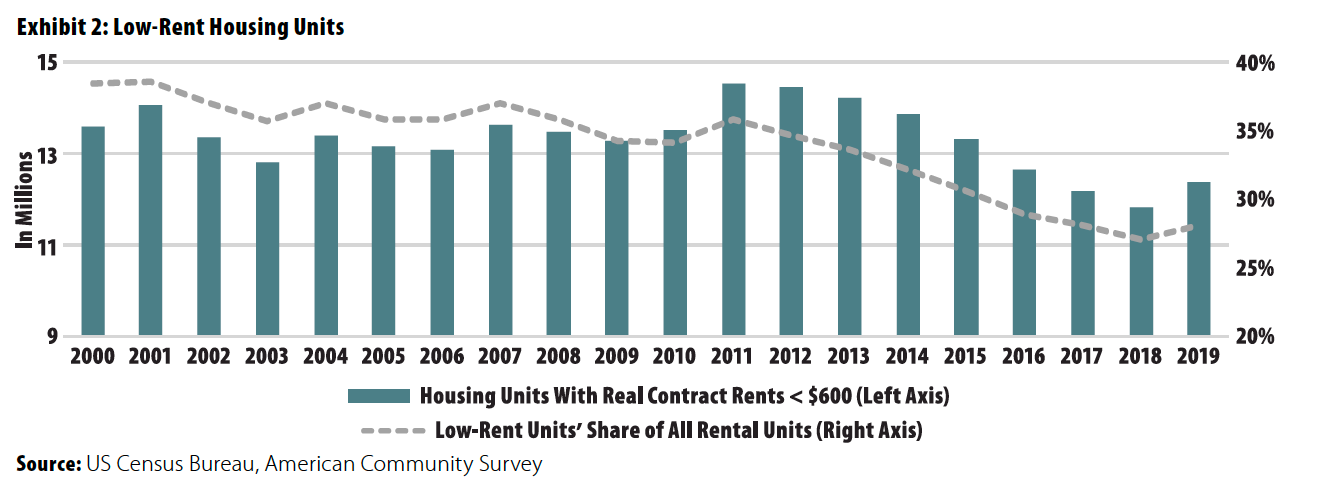

The strong and growing demand for affordable rental housing has not been matched by sufficient supply (Exhibit 2). The National Low Income Housing Coalition estimates that only 60 affordable units are available per 100 households at or below 50% of AMI and only 37 units per 100 households at or below 30% AMI. The supply of low-rent units decreased by 2.2 million between 2011 and 2019, falling from 36% to 28% of all rental units. Much of this supply decrease was driven by obsolescence and by conversions of affordable units to market-rate units.

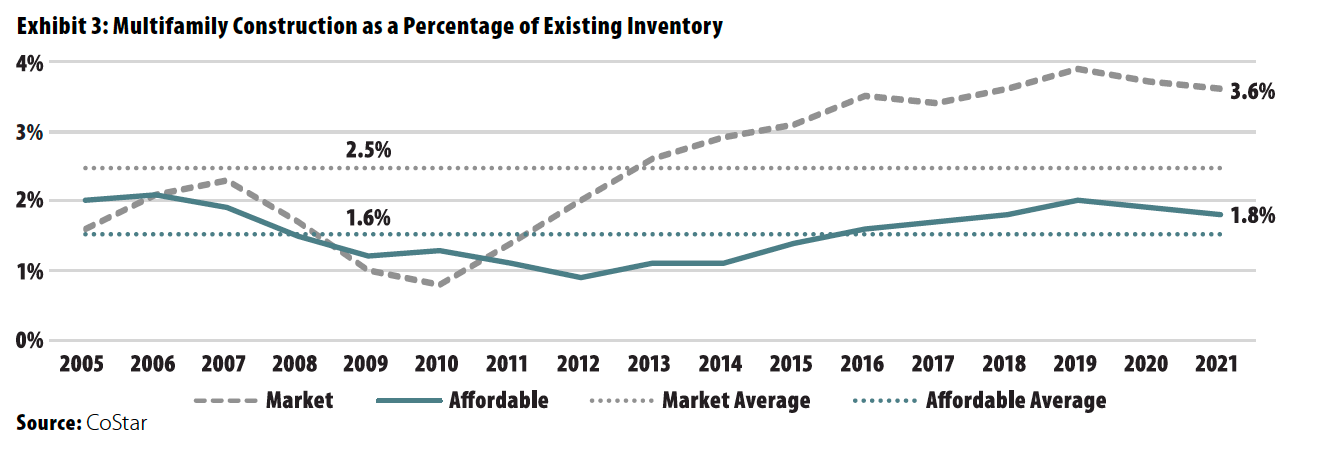

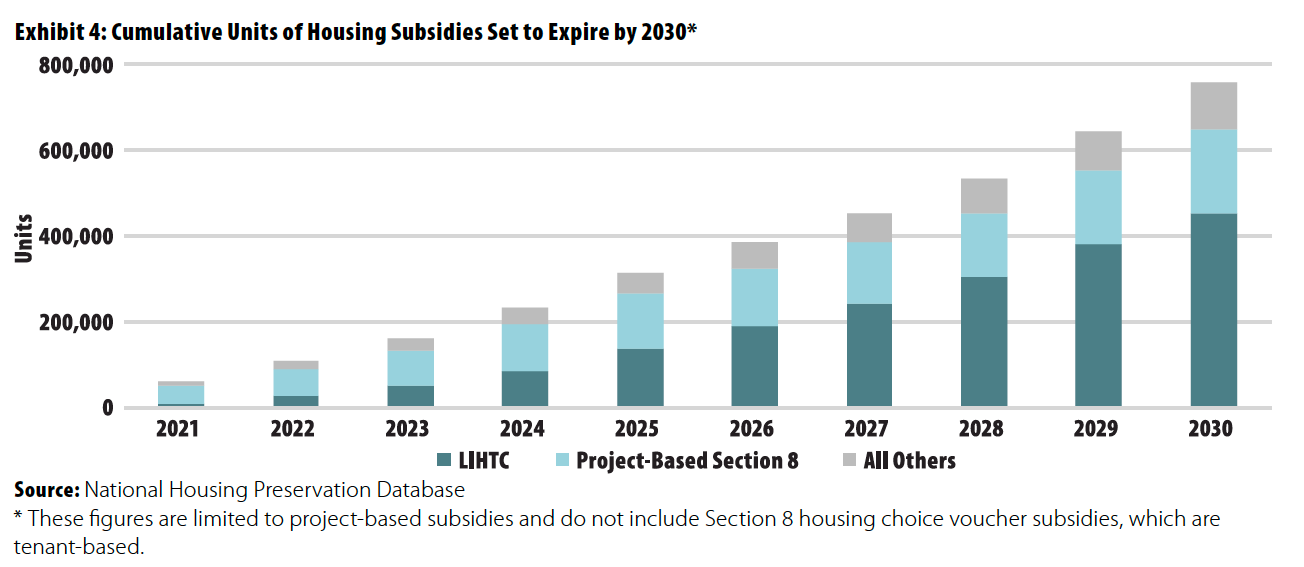

Construction pipelines and subsidy expiration schedules indicate that this undersupply will persist. More than 70% of new apartments under construction are high-end units, and as Exhibit 3 illustrates, market-rate construction outpaces affordable construction relative to existing inventory of each product type.3 These trends are expected to continue as developers prioritize luxury buildings with modern amenities. In addition, expiration of existing affordable housing subsidies will constrain supply. By 2030, subsidies will expire for nearly 750,000 units currently benefiting from federal project–based affordable housing programs (Exhibit 4).

Current levels of new affordable housing supply are unable to keep up with demand for the product. Provided returns are sufficient, this presents an opportunity for investors to diversify into the space, either through development, which offers substantial tax credit opportunities, or through acquiring and rehabilitating existing inventory, which is a lower return-risk alternative.

Market Fundamentals

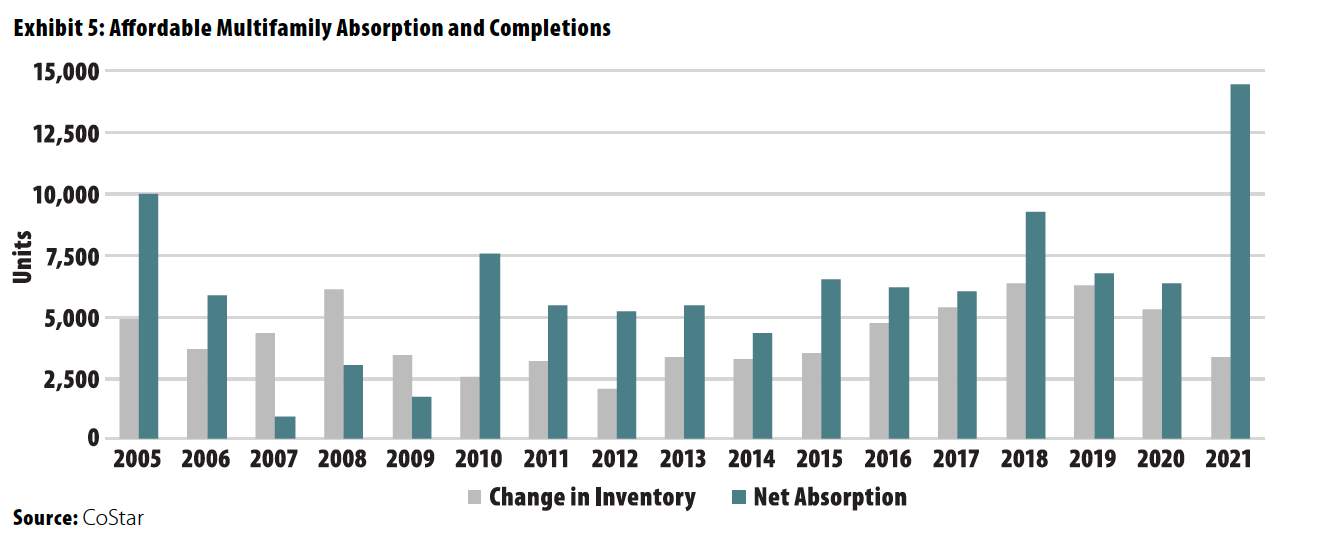

Net absorption of affordable housing has outpaced the change in inventory every year since the end of the financial crisis (Exhibit 5). This favorable supply-and-demand imbalance has led to low and stable vacancy rates and consistent rent growth. Affordable multifamily vacancy rates have consistently been lower than market-rate vacancies. From 2000 to 2021, affordable multifamily vacancy rates were, on average, 180 basis points (bps) lower than market-rate vacancies in the US, according to CoStar. This trend holds across a diverse subset of large apartment markets, indicating that affordable housing is undersupplied nationally.

High demand and low supply have also produced predictable rent growth. From 2001 to 2010, affordable housing rents grew at nearly identical rates as market rents. After 2010, growth rates began to diverge as market rents expanded more quickly; however, CoStar data show that, with the onset of the pandemic, market rent growth also contracted more dramatically. Recently, market-rate multifamily rents have seen record high growth.

Affordable housing also offers investors generally attractive pricing compared to market-rate multifamily. Real Capital Analytics notes that cap rates were consistently higher than market-rate apartments, with an average spread of 40 bps, from 2011 to 2021. Although affordable apartment cap rates compressed with the broader sector, they remained above market cap rates. Higher yields plus favorable supply-and-demand dynamics resulted in increasing investor activity. Annual transaction volume for affordable multifamily increased from $1.3 billion in 2011 to $36.1 billion in 2021 (Exhibit 6). This represents an average compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 39%, more than 2.5 times the 15% CAGR in market-rate transaction volumes over the same decade.

Data on affordable housing returns are not readily available. However, there are several ways to earn returns in the space. On the direct-real-estate-operations side, target returns often range from high single digits to mid teens. On the financing side, private equity funds in affordable housing often target leveraged cash-on-cash returns of 5% to 7%, the same returns generally earned by tax credit funds that finance LIHTC developments. Although these returns are lower than many alternatives, affordable housing investors stress the long-term stability and predictability of returns.

Risks

The affordable housing sector is not without risks and challenges. Development is often difficult because of zoning restrictions, high land and construction costs, and competition with value-added investors seeking to convert affordable units to market-rate units. Federal subsidies are designed to help affordable housing developers overcome these hurdles, but subsidies are highly limited. The ratio of LIHTC applications to credits available frequently hovers around 3:1, according to CohnReznick. Despite affordable housing’s low delinquency rates, low annual increases in allowable rents combined with increases in operating costs and capital expenditures can limit cash flow. Additionally, investors bear headline risks associated with evictions and rent increases. Although these risks are not necessarily prohibitively high, investors must weigh them against the benefits of entering the affordable housing space.

Conclusion

The data and analysis show that affordable housing enjoys two highly desirable real estate characteristics: persistent unmet and growing demand and highly constrained supply. This imbalance has consistently kept vacancy rates low while still delivering stable rent growth, and supply pipelines suggest that the gap will not close anytime soon. With moderately elevated cap rates relative to market-rate apartments, affordable housing offers investors an opportunity to realize stable risk-adjusted returns in a recession-resistant asset class.

In addition to these traditional investment benefits, affordable housing also yields social benefits, which are increasingly important in today’s investment environment because of the growing emphasis on ESG goals and impact. This analysis suggests that investors need not forgo competitive risk-adjusted returns to pursue these broader social goals. Affordable housing offers institutional real estate investors an opportunity to generate stable financial returns while simultaneously providing important social benefits.

1. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Federal Housing Finance Agency, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Housing indices are inflation-adjusted with CPI-U. All items are US city averages.

2. National Multifamily Housing Council, US Census Bureau.

3. High-end units are defined as CoStar 4 and 5 Star rated buildings.

Scot Bommarito is a Senior Research Associate and William Maher is Director of Strategy & Research at RCLCO Fund Advisors.

This article has been prepared solely for informational purposes and is not to be construed as investment advice or an offer or a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument, property, or investment. It is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for, tax, legal, or accounting advice. The information contained herein reflects the views of the author(s) at the time the article was prepared and will not be updated or otherwise revised to reflect information that subsequently becomes available or circumstances existing or changes occurring after the date the article was prepared.

About PREA

About PREA